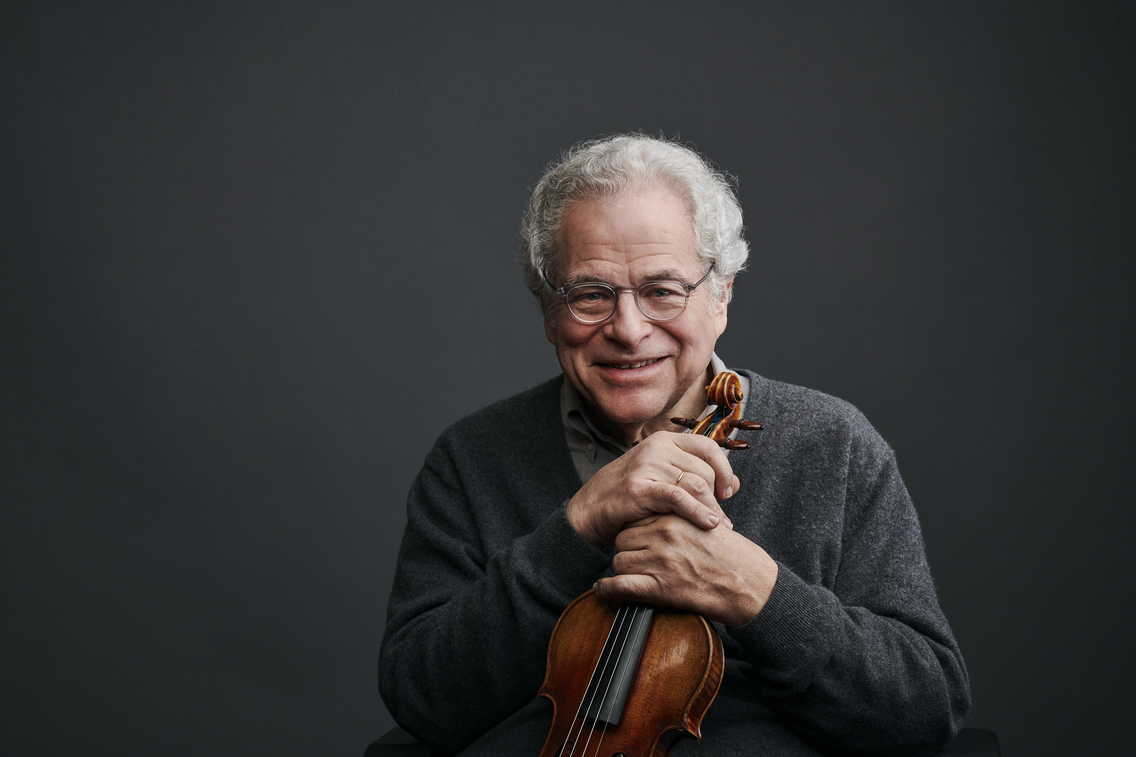

Itzhak Perlman: The Legendary Violinist at 80

Nikita Solberg

Nikita SolbergIDAGIO met with the renowned violinist Itzhak Perlman in celebration of his upcoming birthday to discuss his life in music, advice for the next generation of musicians, and the legendary tale of how he acquired his Soil Stradivarius.

There’s the saying "never meet your heroes," but do you have a story of meeting someone that you admired and it being a positive experience?

I don't know about heroes, but it was the most exciting thing when I played Igor Stravinsky’s Violin Concerto. I played his concerto when he was still conducting programmes and I felt that I was quite young; I was twenty-two. To meet this giant composer that was at my rehearsal listening to the way I played his own concerto, it was just very, very exciting. That’s one of the first experiences that I had, where it was like meeting Beethoven.

Do you have anything to share about the rehearsals with Stravinsky?

Well, he liked how I played. As a matter of fact, it was even mentioned in the book [Stravinsky: Discoveries and Memories] by Robert Craft, who always worked with Stravinsky. He mentions how I played this concerto and it was such a wonderful little mention, it's such a compliment.

Stravinksy was a great fan of the Baroque and in the concerto there's quite a lot of Baroque tastes, especially in the third movement. He was also a great fan of humour and rhythm. When you listen to a lot of his works, whether it's the Rite of Spring or Petrushka, he does a lot with rhythm. Rhythm is also featured in the Violin Concerto, and I just love that piece.

In the rehearsal, Stravinsky made one little comment to me to play a little bit slower in one bar. He said, "Can you do that a little slower?" That was it and he liked it. I was very, very happy with it.

That's the best compliment we could imagine getting from a composer.

And not only that, it was in Honolulu! We were photographed together with those flower leis on and the two of us having a fun time.

What is on your listening list for this week?

What comes to mind? My goodness. Maybe I would love to listen to some opera arias sung by some wonderful tenors. I'm a great fan of the tenor and soprano voices. I'm a fan of singers so perhaps an aria from Don Giovanni, or an aria by Puccini or Verdi, and of course from Pavarotti, Björling or Corelli. I love to listen to spirituals from Marian Anderson. There's an album by her with the wonderful viola player, William Primrose. They made a recording of a couple of Brahms songs which are absolutely phenomenal. I would love to listen to that—I always listen to that album because I love it. Plus there are some terrific recordings that Bernstein boy made.

And do you have any non-classical recordings that you like to listen to as well?

I love to listen to a lot from the 50s and 60s. I put on the radio and then listen to just about everything, whether it's Paul Anka or Neil Sedaka, Elvis, Ray Charles, the Diamonds. I love Billy Joel and the Beatles as well.

How do you balance your time in and outside of the practice room?

I didn't really like to practise when I was growing up. For my parents it was always the number one topic, how much was I practising. When I started to play concerts, I stopped practising because I wanted a rest from all of that pressure. I didn't want to practise. But as I'm getting older, I realised that practising is actually good; it is very helpful, and you can feel it. Now I practise to the point that I can say, “I can still play you.” I put the violin under the chin and I play for about 10 minutes. When I can say, "Yeah, it's still there," then I put it back in the case.

That makes sense, to have mindful and productive practice. Besides practising, what are some necessary activities you recommend for musicians to develop their musical voices and opinions?

Listen to everything! Listen to new stuff, listen to opera, and listen to orchestral music. I love to listen to jazz, and made a few jazz recordings. I'm not a jazz player, but I enjoy it. I made a recording with Oscar Peterson—he’s an absolutely fantastic pianist.

Art Tatum is another pianist that struck me many years ago. There was a recording of him playing the Dvořák Humoresque and I said, "Who is that?" I had never heard of him before and then realised why he was so very respected, even by people like Vladimir Horowitz, who thought that his technique was quite phenomenal.

It's always fun too to try and guess who is playing, especially when you listen to orchestras. Which orchestras can you recognise? Can you say if it’s the Philadelphia Orchestra or the Cleveland Orchestra? The other day I was listening to a recording of Brahms’s Third Symphony and I wondered who it was, since it was very slow. It was Bernstein conducting the Vienna Philharmonic. When it's really good though, you always think about how there is never such a thing as the right tempo. It can either be very fast or very slow, but if it works, if it makes sense, then that's it. A lot of music is all about timing. I suppose timing is something that is very important, not only in music, but in everything else, like comedians and how they deliver their comedy, or people in theatre.

There has been discussion nowadays that with so much music being immediately available, a lot of the orchestras have lost their signature styles and sound more similar. Would you say you agree?

That's actually true. Right now the recordings are less individual, but orchestras can still sound really terrific. The other day I was listening to a recording from a non-major orchestra but my wife and I both said that it was quite fantastic, absolutely amazing. It was not one of the top orchestras in the US, or the big ones in Europe. You could also say that the level of orchestras has gone up. In the States, it used to be that you only had a few top orchestras and then the rest were okay. But now you have an awful lot of orchestras that are in secondary cities who sound like a million bucks. A lot of it has to do obviously with the conductors, and with the quality of the players.

I can tell you that for auditions, orchestras demand a higher quality than ever. For violinists, the demand is unbelievable; you can no longer say that 'good enough' is sufficient for a even a second or third stand. As a result, the string sections of the orchestra are sounding terrific!

For very talented young string players my wife started a programme called the Perlman Music Program. We listen every year to on hundred violin applicants but only have an opening for four or five. The quality of those applicants is phenomenal, it makes it so difficult! Who do you choose? Out of one hundred applicants you can have sixty people who could get into our programme with no problem. But if you have only five openings what do you do? You must be a little more careful in what you're looking for. You're looking for somebody that would inspire you, because technically the level is as high as it has ever been and everyone has become so good. A lot of people start to say that classical music is in trouble, blah blah, blah. Not from where I'm standing.

That's an optimistic mindset to have! There have been articles for decades saying that classical music is dying. Of course there are challenges, but what is your advice? Is it really as bad as they say?

I don't think so. I think you can succeed if you know what you're doing and what kind of programme you're choosing, since it has to be a mix. It should not just be a programme of music written today, or a programme written one hundred years ago. It has to be a combination of works. If you know how to programme, it'll bring the audience in.

Nowadays a lot of musicians have to wear many hats. Do you feel like there are specific things that musicians can do to be more prepared once they finish their schooling?

That's a very good question! One of the great challenges in life is to make a living at something that you like, as opposed to making a living at something that you have to do in order to make a living. I keep saying to my students, we should all feel very lucky that we are in this kind of wonderful profession. My advice is always this: don't look at one thing and say that if you can't do it, that's it. There are so many possibilities in music whether you are playing solo, chamber, in an orchestra, teaching or promoting music; there are so many possibilities. Don't have blinders on and think that if you cannot do this one thing, you are stuck. I find that a lot of my students have variety in what they’re doing, and being a good teacher for them is an art form in itself.

You should do something that you're good at, that gives you pleasure. For me that would be my kind of complete success. You want people who are really proud of what they do and who feel that their work is important. Then you have musicians full of pride dealing with the great works of art, dealing with masterpieces. How much better can it be? It's fantastic just to listen to a Brahms symphony, a Mahler symphony. But if you can be proud of taking part in that amazing process by playing, it's phenomenal.

It’s also our cultural inheritance to be able to have the chance not just to listen to it, but the chance to play it, to discover more about yourself and to discover more about life.

Exactly. About the availability of music, I’ll always remember at Juilliard when I wanted to listen to a recording, there was a special room that had record players. There was a library and you would pick an album, put headphones on, and you would listen to it right then. If you wanted to listen to something, you had to go and get it. But what we have available is fantastic: we can listen to things that are not just current but also sixty or seventy years old.

At the Pearlman Music Program, we have a programme where we listen to recordings – or, if they’re available, videos of older artists playing – to study music history. The way we play today has everything to do with how our playing has evolved over the last fifty years. If you're talking about horn players, listen to Dennis Brain and how he played, and then compare that to what kind of sound is produced today from horn players.

I'm not a horn player but sound is overall everything that I believe in. Whether it's the sound of a horn player, the sound of an oboe player, a violinist or a singer, it's all about what kind of sound you are producing. That's the first thing that hits your ear, the sound. It might be that you don't agree with the person musically, but you've got to listen because of the sound.

We’re always curious to learn how people experience music in that way. Do you feel like listeners only go after the orchestras or conductors they really like? When there are so many options, how do you choose what to listen to?

I always push my students and those in the programme to listen to how musicians used to play. The style of players has changed a lot, it has evolved a lot. For example, I play klezmer and it's fun to listen to old recordings of great klezmer players and hear how they did it then.

It’s so important to listen to the great violinists from the 1920s and 30s, like Fritz Kreisler for example. Kreisler had the most amazing, incredible sound, but his style was different. From his style, violin playing as a whole developed. Jascha Heifetz came along and sounded a little bit like Kreisler at the beginning. But as he grew older, he became his own kind of person and developed the sound that we know. When he was starting he had to play whatever he had in his ears, since there wasn’t a lot unless you went to concerts. You couldn't just turn on the radio or internet and listen to anybody you wanted. It had to do with who was in his class, what kinds of concerts he had in his city and what style that people played at that time.

You can learn from anything, but you should always learn. You don't have to imitate but you can learn because they had a particular way of turning a phrase; it has again to do with the timing. A successful performance of anything has to do with how the timing works. You can have something that sounds perfect and yet you're sort of not sure. It can sound okay, but something is missing. What's usually missing is the timing. When all is timed just right, it makes you listen and say, "God, that really works." But it can also be very difficult.

Things can seem simple. Take one of Beethoven’s great violin concertos, for example: there are a lot of scales and arpeggios—what are you going to do? It involves how you start a phrase and how you finish a phrase. To make that piece work there are first the technical and intonation aspects, because it's so transparent, and second the timing of the phrases.

Speaking of repertoire, was there a piece of music that you weren't so fond of at the beginning of your career that you discovered or fell in love with later in time?

The first thing that comes to mind is the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto. I played it as a student and anything that you play as a student always has the danger of having whatever weaknesses you had then. Let's say that there were notes that have always been out of tune, when you bring it back those notes are automatically out of tune unless you fix it. Sometimes students come to me saying they played this piece when they were younger, and to me that means I have to get rid of all the bad habits they had then, but also now.

With the Mendelssohn, I had played it but I was kind of tired of it, so I stopped playing it. But after about five or six years where I wasn’t playing it, suddenly I discovered that it was the perfect piece. I made the point that anything I recorded or played, I would do because I like it, not because I have to. It's because I believe in the piece, which you have to when you're playing the piece over and over again. One of the great things is that if you are really into it, you can play a piece and still make it sound spontaneous. It's not the first performance, it's the third and fifth and sixth performance of the same piece. When the piece is great like the Mendelssohn Concerto, you can play it and perform it every day.

I always say, don't do it the way you did it yesterday. Everything should be a fresh experience. When you play a piece for the first time, in some ways it's easier to play it because it's all very exciting and new. The challenge is the second time: do you do it the same way? And when you change it – I'm not talking about black and white, I'm talking about subtleties or colour changes that you haven't made before – it's a lot of fun to do. When you make a recording, it is an example of the time in which you recorded it. In other words, that's the way you liked the piece at that time. Then you play the concert and sometimes people will come backstage and say that it wasn't the same as the recording, and I say, "Thank you."

That's one of the great things about playing live music: you're listening to something you haven't heard before, and you wouldn't hear it again exactly the same way. The wonderful thing about a live concert is that it's something individual, of that moment. Every time you play, you rediscover the piece in front of the audience. I speak to the audience through my music: this is my opinion of this particular piece at this point in time, and that's the way I like it.

In regards to your Soil Stradivarius and how you purchased it from Yehudi Menuhin, can you share how that transaction came about?

At that time we were young violinists who actually had the luxury of saying, "I heard about this great Italian violin, or Stradivarius, or Bergonzi, or any of the great makers; maybe I can purchase it.” At that time, if something was expensive, it wasn't that expensive. Right now, forget about it. It's very unfortunate for young string players today.

With my Strad, I was actually looking for a Guarneri that I heard was absolutely fantastic and I was wondering whether it was for sale. Finally someone said to me that Menuhin knows the person who actually bought that Guarneri. After all this searching, I was dying to see the violin even though I couldn't purchase it. I visited Menuhin at the Yehudi Menuhin School—I had known him since I played for him when I was eleven or twelve years old in Israel. He was a really wonderful gentleman and I asked, "By the way, what violin do you play on these days?" He took out the Soil, the Stradivarius. I asked if I could play a couple of notes and of course he said yes.

I played about five notes. I thought I had died and gone to heaven. I couldn't believe it. It was the most amazing, immediate sound; it was like it went into my gut. So I said, "Thank you so much. If you ever think of selling it, can you sort of keep me in mind?”

One morning, I got a call that the violin was for sale and that it was actually offered to somebody else, and the friend that let me know said he went to Menuhin’s house and took the violin to make sure it didn’t go anywhere. My friend said, "Either I buy it or you buy it, but it doesn't leave my house unless it goes to one of us." And that's it.

But we had just bought a house and had no money, so we made another loan. I paid it off about five months ago. No, I'm just kidding, but I did finally pay it off, and that violin is my baby. It's an amazing fiddle. Even for all that money, I would spend it again just to look at it, forget about playing it. The violin is so beautiful. It's a 1714 golden period Strad. I don't care how it sounds, if it sounds good, it’s the icing on the cake.

Menuhin was not too happy to part with it, but he had to. We would send each other New Year's cards and every time he would send me a card, he would ask, "How is our violin doing?"

Itzhak Perlman's Complete Recordings on Deutsche Grammophon & Decca is out on IDAGIO now.